I came to appreciate the value of documenting speech patterns, especially those spoken by people for whom English is a second language. I grew up in Sheboygan, Wisconsin where I heard German spoken on the bus, in the butcher shop, and at the Five and Dime every day. In the 40’s and 50’s, “Vas ist Los?” and “Guten Tag,” were every day phrases. And whenever I overheard my German neighbors converse in English, they would say, “How’s by you?” instead of “How are you?” But by the time I visited my hometown a decade later, all these German/American phrases had disappeared with the babushka. To this day, I regret not jotting more of them down before they vanished from our lexicon.

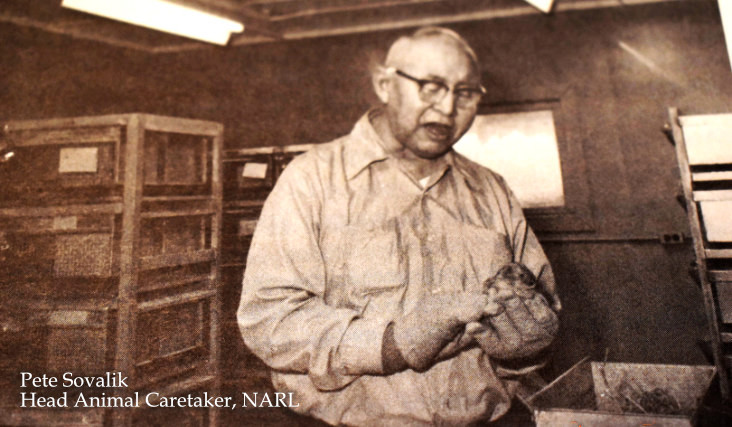

However, I tried to follow the writing instructor’s example years later when Pete Sovalik, head animal caretaker at the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory began telling me Iñupiat stories. It would not have been considerate to scribble down those stories on the spot. Instead, I would listen intently, then race back to my Quonset, drag out my Smith-Corona typewriter, and type them up while I could still hear his voice in my head. Forty years later, I found those hastily typed stories from 1969 in a 3-ring binder, single-spaced on notebook paper turned yellow over time. This treasure trove of stories became the voice of Ben Ningeak, Jesse Bookman’s Iñupiat friend and mentor in my novel. In addition, I drew from his stories to weave a unique Iñupiat thread throughout the book.

When I began writing dialog for Bear Woman Rising, I tried to capture the speech patterns I heard during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s from the Iñupiat for whom English was a second language. That unique blend of Iñupiat and English has largely disappeared over the last 50 years. But back in 1969, as I worked alongside Iñupiat villagers in the Arctic, I heard abbreviated versions of the English they’d learned informally. For example, one day, as I attempted to carry my lab supplies to a new space in one trip, I kept dropping them. Isaac Patkotak, intrigued by watching a crazy white woman trip over the stuff that flew out of her arms, stopped what he was doing to help. He handed me my lab notebook and asked, “Why you no go back and forth?”

Why indeed, Isaac?

Out of a deep respect for the Iñupiat and their culture, I tried to preserve Pete’s speech patterns as authentically as I could in Bear Woman Rising. I am proud to open my novel with the following Inupiat tale as told by Mr. Pete Sovalik.

Iñupiat hunters walk out on tundra, watch for caribou.

Stand on cliff, high place of looking, watch for whales.

What hunters do.

Go to new place, look around.

Come back, tell people what they see.